This is an extract of an article that appeared in Ancient Egypt 132. Read on in the magazine.

The Tomb of Maiherpri

Dylan Bickerstaffe investigates the discovery and documentation of Tomb KV36 and assesses what we now know about “The Lion of the Battlefield”.

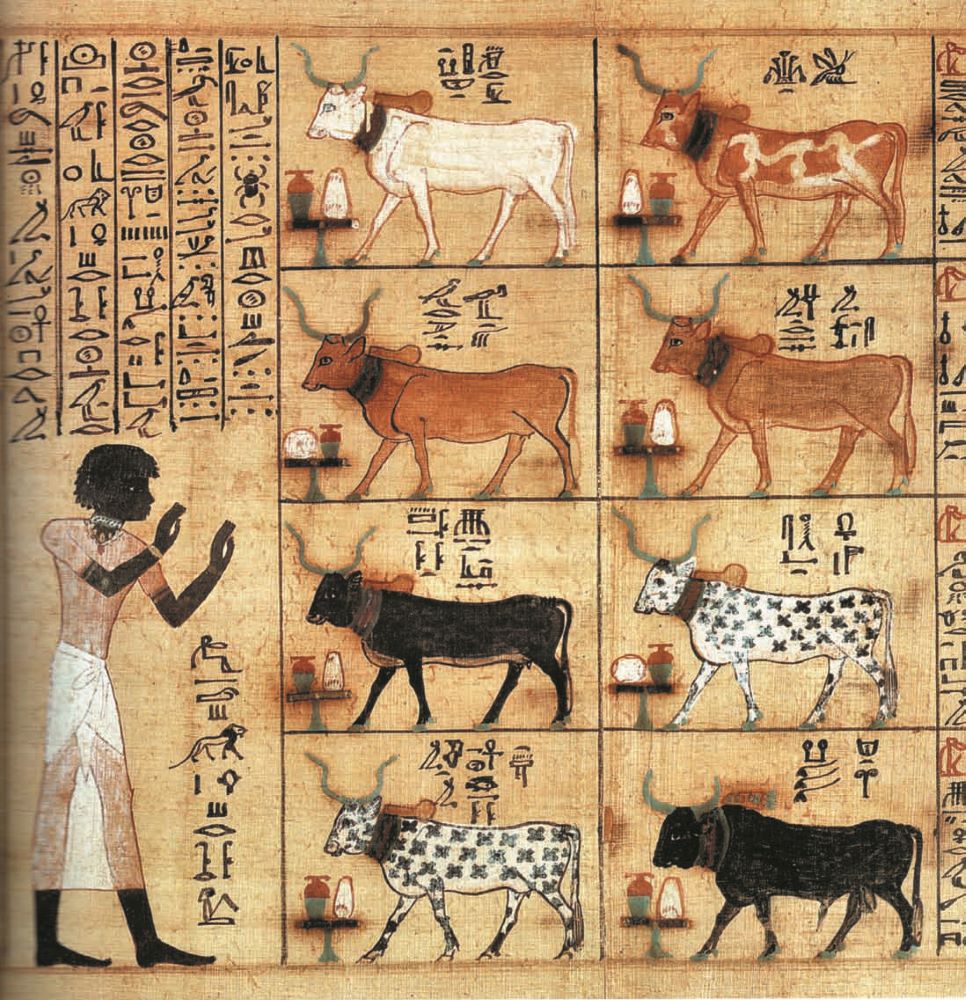

Maiherpri depicted in his Book of the Dead papyrus.

During his brief tenure as Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service (August 1897 - late 1899), Victor Loret spent most of his time conducting excavations. The highlight of this was undoubtedly his work in the Valley of the Kings where, in a little over a year, he discovered six new tombs, including those of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs – Thutmose III (KV34); Amenhotep II (KV35, which included the second cache of royal mummies); and Thutmose I (KV38) – thereby proving that the main valley was not just a cemetery of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasty ‘Ramesside’ pharaohs.

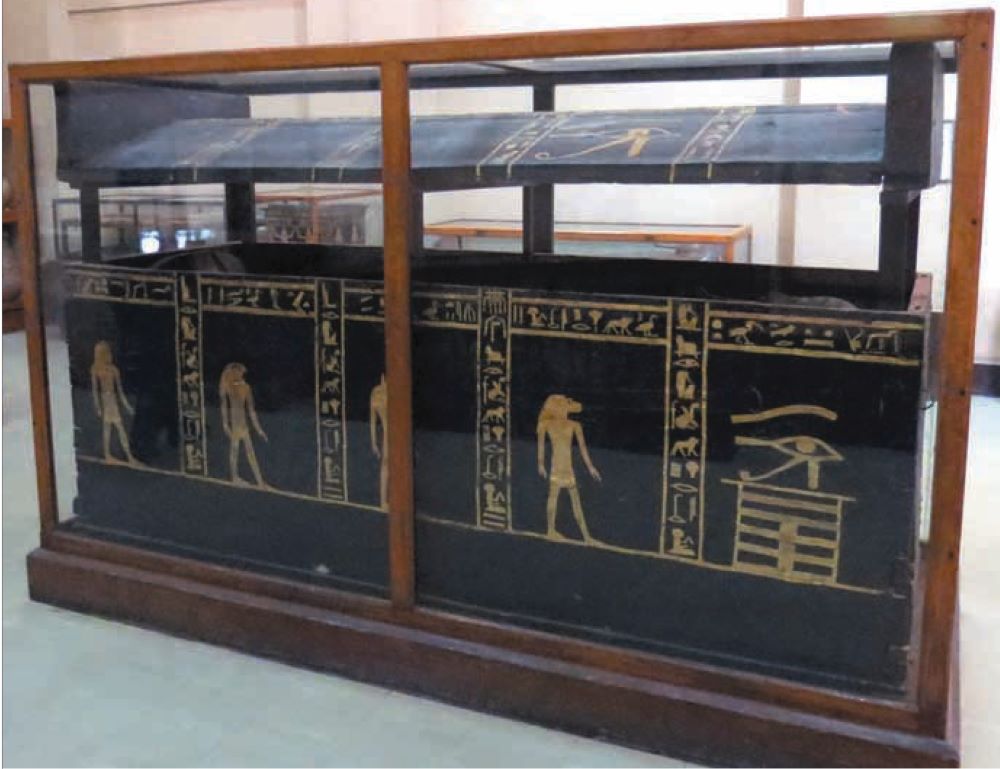

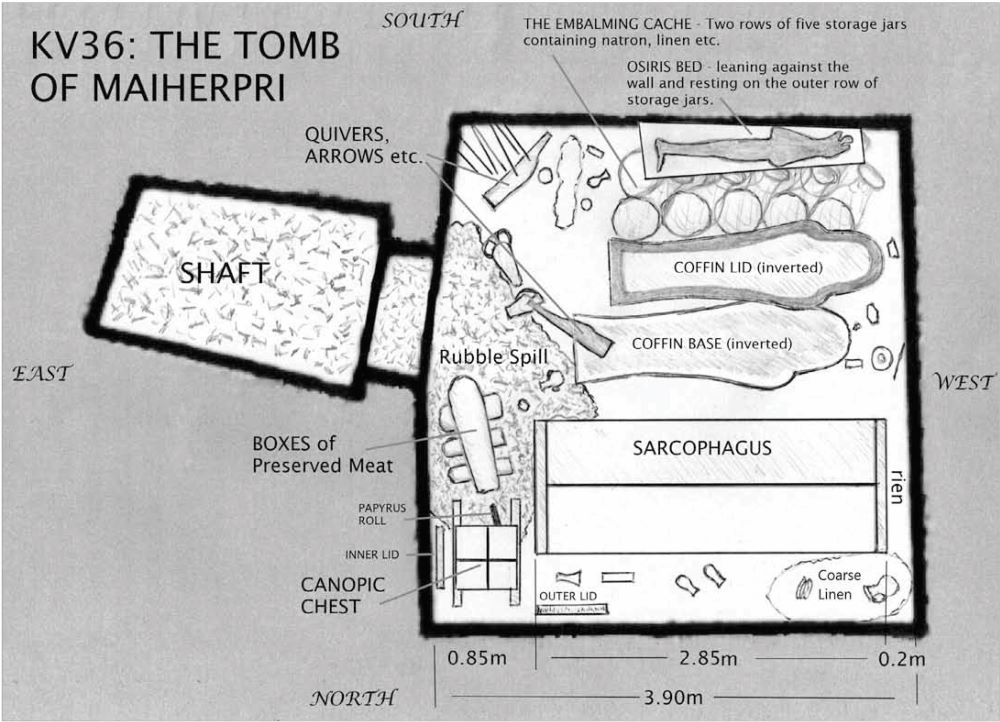

Excavations to the south of the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV35), and near the main axis of the Kings’ Valley, led to the discovery of a small undecorated shaft tomb (KV36). On March 30th 1899, Loret was able to descend the vertical shaft, look into the single chamber at the bottom, and so become the first to discover a substantially intact burial in the Valley of the Kings – that of Maiherpri. Virtually the whole of the floor area of the chamber was filled with artefacts – clearly disturbed, but relatively intact.

Unfortunately, Loret (who was a very diligent excavator and record-keeper) was soon driven to resign from the Directorship and left for France to pursue a career in lecturing, leaving the tombs of both Maiherpri and Thutmose I unpublished. Until recently, the location of objects within Maiherpri’s burial chamber could only be vaguely hazarded from brief comments in the museum catalogue prepared by Georges Daressy, and from some general points written ‘for popular consumption’ (published in the journal Sphinx) by the German explorer and botanist Georg Schweinfurth, who had visited the tomb during the clearance of objects. He mentioned that a lidless coffin lay “inverted in the middle of the chamber”, but sadly only gave the location of most items in relation to a large box sarcophagus – the position of which was never stated! He said that a gaming board and related pieces were found “between the sarcophagus and the wall of the chamber”, with boxed provisions and garlands “in the northern corner behind”; and that thirteen large storage jars containing refuse embalming materials were “on the wall opposite the sarcophagus”. Other clues were nothing more than fuel for the imagination: “… strange weapons and works of art have been brought to light in the burial chamber …”.

This was the position which confronted Egyptologists until 2004, when Patrizia Piacentini of the University of Milan discovered Loret’s notebooks in the Archives of the Institut de France – at the Academie des Inscriptions et BellesLettres, Paris. These sketches were published in La Valle Dei Re Riscoperta (2004). Among the discoveries were Loret’s annotated sketch-plans, carefully recording the location of items within Maiherpri’s tomb and occupying pages 13-30 of his Carnet (notebook) II. From these notes it is clear that he started by recording the layout of objects visible when the tomb was first entered on March 30th 1899, and then made additional notes as items were cleared to reveal others concealed beneath and behind them.