Saints or Sinners? Scandals among the servants of God

Economic records indicate that the priesthood was a major institution in ancient Egypt. The Abusir Papyri reveal that long after the death of the Fifth Dynasty ruler Neferirkara (c.2475-2455 BC), there were between 250 and 300 individuals associated with his funerary cult at his temple at Abusir. The Great Harris Papyrus informs us that, at Karnak during the New Kingdom more than 80,000 people (not all of whom were priests) either worked at the temple, or were associated with the landholdings and temple workshops – all dedicated to the purpose of maintaining the domain of Amun.

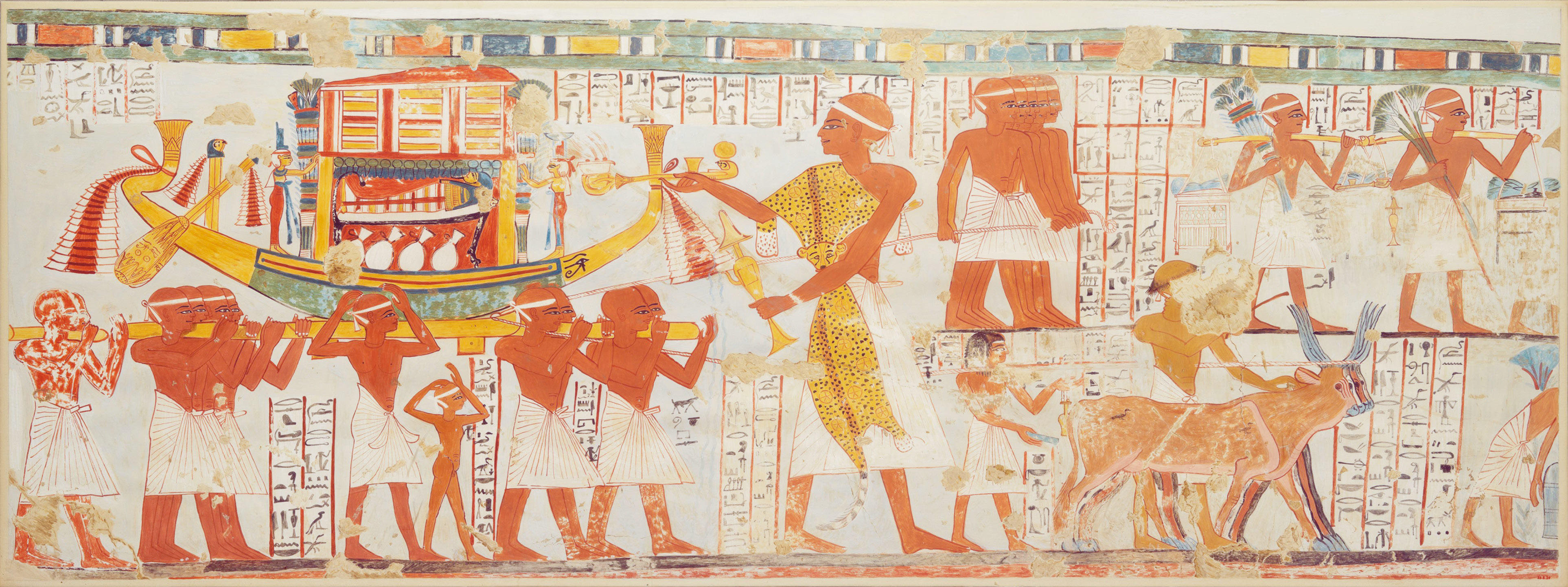

A facsimile painting from the Nineteenth DynastyTomb of Nakhtamun (TT341) showing priests conducting the funeral of the deceased man. Image: Nina de Garis Davies, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

We have the names and titles of numerous priests, as well as very many biographies describing their duties. In countless scenes they are depicted performing ritual activities, and are frequently portrayed in temple processions. Many of the priests were the sons of former priests, but some were appointed to their ranks, and priestly positions could be purchased. Being a member of the priesthood was a valued occupation due to the wealth and power associated with this role. It would seem quite likely that many of the priests were honourable officiants, but, unsurprisingly for such a large institution, the priesthood did include unsavoury characters among its number. There appeared to be few checks on the suitability of individuals for the priestly life, and little is known of any preliminary training that may have been required in order to be admitted into their ranks. This lack of selectivity may have been a factor helping to explain certain shocking episodes in the history of the ancient Egyptian priesthood.

Scandals at Elephantine during the Ramesside era

Elephantine, or Abu, was the capital of the first Egyptian nome and, here on the island, the ram-god Khnum was the principal deity. At the end of the New Kingdom, during the reigns of Ramesses IV (c.1153-1147 BC) and Ramesses V (c.1147-1143 BC), a number of scandalous activities occurred in the temple dedicated to Khnum at Elephantine, as attested in the Turin Indictment Papyrus (P Turin 1887). The document details how a number of denunciations were made by a certain Qakhepesh, a ‘God’s Father’ at the temple. Qakhepesh accused a wab-priest, Penanukis, of bribery, sexual misdeeds, causing an abortion, intimidation, theft of temple property, disrespect for the sacred space, and manipulation of the oracle. Penanukis was also accused of brutality, including burning a house, blinding of two women, and cutting off someone’s ear.

Priests carrying a festival barque in a relief from the Ramesseum, the funerary temple of Ramesses II. Image: Steve F E Cameron, CC BY 3.0, via Wikicommons.

Penanukis was the ringleader of a group of priests who, with a local boatman, were listed as complicit in these crimes. When other priests at the temple objected to their nefarious activities, Penanukis and his colleagues were able to remove them from office, and bring in other priests who were seemingly more amenable to their corrupt activities. They accomplished this by oracular decision, with Penanukis placing himself at the front of the litter carrying the sacred barque, and guiding its movements to ensure the judgement went against the demurring priests.

Eventually, the matter was investigated by the scribe of the temple, Montuherkhopshef, who also acted as the chief of police. However, Penanukis and his colleagues were able to bribe him, and so their thefts and misdeeds were allowed to continue. Even when Montuherkhopshef was appointed Governor of Elephantine, it would seem he continued to accept bribes and took no action against the culprits.

The remains of the Temple of Khnum on Elephantine Island. The priests of this temple were involved in a number of infamous scandals in the Ramesside Period. Image: Sarah Griffiths (SG)

In the end, the inertia of the local hierarchy alerted the central power, who instigated an inquiry, and the overseer of the ‘White House’ (the treasury), Khaemtyr, was dispatched to investigate. Unfortunately, the extant texts do not inform us of the outcome of the inquiries, and so it is not clear if Penanukis and his collaborators were punished for their crimes. This series of events, occurring as it did near the end of the Ramesside Period, also demonstrates the weakness of central authority at the close of the New Kingdom.

Drunkenness

There are indications that some members of the priestly class knew how to appreciate good food, lift a glass or two, and live well. During the Graeco-Roman Period, two friends of Ptolemy XII Auletes (c.80-51 BC) – Setna and Pasherenptah the High Priest of Memphis – were welcomed to a celebration by the priests of Koptos. According to an inscription on the funerary stela of Taimhotep, one of the wives of Pasherenptah, they clearly had a good time:

Oh, my brother, my husband friend, high priest! Weary not of drink and food, of celebrating deep and loving! Celebrate the holiday, follow your heart day and night, let not care into your heart, value the years spent on earth!

However, such celebrations may not have been the norm. An instruction in the Temple of Edfu, also dated to the Ptolemaic Period, tells a different story:

Oh, great prophets... Do not sully yourselves with impurity… Let there be no festivals in this temple… Do not open a jar…

This latter inscription may also have been a reference to festivals of drunkenness, which are attested from the New Kingdom onwards, if not earlier. Specific religious festivals were associated with intoxication, and often linked to Hathor. Hatshepsut built a ‘porch of drunkenness’ in the Temple of Mut at Karnak, and there is prolific evidence concerning the festivals in Ptolemaic temples. The festivals involved communal ritual activity, as well as drunkenness, and at times sexual activities. However, festivals of drunkenness seem to have been frowned on in some of the temples, and by certain members of society.

Petition of Petiese

Petiese III was descended from a once-powerful priestly family who had settled in Tayu-djayet (Teudjoi, modern el-Hiba) during the reign of Psamtek I (c.664-610 BC). The family members lived on the priestly benefices or stipends accruing to their priestly duties, but the source of this income was contested by the priesthood of Amun. In 512 BC, during the reign of Darius I (c.522-486 BC), Petiese III recorded the history of this disagreement which, amazingly, had been ongoing for nearly 150 years (P Rylands IX). It is an extraordinarily long and complex story, in which the priests of Amun, over several generations, attempted to resolve this dispute by disreputable methods, including theft of priestly benefices, bribery of officials, conspiracy, embezzlement, and even violence and murder. This is far from an image of piety and moral activity among the ranks of the priesthood, and, if the account is to be believed, it would seem only bribery and violence brought results.

Reversion of offerings

An essential element of the remuneration of priests was the food offerings that were presented to the deity three times a day in the temples of ancient Egypt – the so-called ‘reversion of offerings’. After a period of time, when it was deemed that the deity had partaken of the essence of the food, the foodstuffs would be taken away, and divided up among the priests and temple staff for their personal consumption. However, this was liable to abuse. Food could be taken away too quickly, before the ritual was complete, while some items may not have been presented to the deity at all.

There are a number of warnings about removing the food too quickly. A text from Edfu states:

Do not go freely to steal his [the god’s] things. Beware, moreover of foolish thoughts. One lives by the food of the gods, and ‘food’ is called that which comes forth from the offering-table(s) after the god has been satisfied with it.

It would seem, therefore, that it was by no means uncommon to remove food offerings, and these foodstuffs may then have been sold or bartered by the priesthood.

Ka-priests

The hem-ka or ka-priests are depicted carrying food and other offerings in scenes representing funerary rituals. They also acted as executors of endowments established to ensure that offerings were left daily in the donor’s tombs, often set up by an individual while he was still alive. However, endowments had the potential to immerse ka-priests in family disputes and were also open to exploitation between fellow ka-priests.

A number of texts indicate the nature of some of these disputes, such as that inscribed in the Fifth Dynasty mastaba tomb of Nyankhamun and Khnumhotep at Saqqara, which reveals friction among the priests:

With regard to any [ka-]priest who shall start proceedings against his fellow priests, whether it be coming forward with a complaint about his carrying duties or producing a document for the discontinuation of the invocation offerings of the owners of this funerary cult. All of his share shall be taken from him and given instead to that [ka-]priest against whom he started the proceeding.

So this would appear to be rather rough justice: if you made a complaint, even if it was legitimate, the judgement could go against you.

Another inscription, found on an offering table in the Sixth Dynasty mastaba of Khentika, again refers to problems besetting ka-priests and the endowments they administered:

With regard to any ka- priest of the sole companion, Khentika, who shall not make the invocation offerings, I shall make him lose his job.

The implication is that the deceased could influence events from the afterlife if the ka-priests did not correctly fulfil their responsibilities.

Harem Conspiracy

Priestly misdeeds were attested, too, at the very highest echelons of power, as recorded in the events of the so-called ‘Harem Conspiracy’. This was a plot against the life of Ramesses III (c.1184-1153 BC) towards the end of the New Kingdom. The primary sources of information about these happenings are the trial records in which 32 men, including stewards, inspectors, a general, and an undetermined number of women, were indicted for their part in the conspiracy.

By its very nature, the attempted murder of a ruling monarch in ancient Egypt would be fraught with many problems. Not only would the ruler be heavily guarded, but he was deemed to be under the protection of the gods. The conspirators considered that there would be little hope of success in this venture without the use of magic, and to that end they enlisted the help of a number of individuals versed in the use of magical practices, mainly the priestly classes. Among them were two lectors, Prekamenef and Iyroy. These individuals, together with many of the others indicted, were found guilty of treachery during the ensuing trials, and were sentenced to death. However, the lectors were allowed to commit suicide rather than suffer the humiliation of a public execution. This was not only an indication of their higher status, but also implies a fear that the magic the lectors were deemed to possess could be turned against the judges and their potential executioners.

The plunder of western Thebes

Tomb robbery is attested from the very dawn of pharaonic civilisation, and during the unsettled times at the end of the New Kingdom, there was widespread plunder of the funerary temples in western Thebes, with the main foci being the Ramesseum and the Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu.

One of the main targets appears to have been the sheathing of precious metals – gold, silver, and copper – that covered many of the architectural elements of the temple, such as the columns, obelisks, and door-frames. Records of investigations into these thefts indicate that the thieves were generally local craftsmen, minor officials, and lower and middle ranks of the priesthood. They seemingly treated these temples as reserves of precious metals to which they helped themselves according to their needs of the moment. They often removed fairly small amounts on each occasion, just a few scissor snips or some small pieces, but over time substantial quantities were removed.

For example, Amenkhau, a wab-priest, removed 300 deben of silver (about 27kg) and 89 deben of gold (about 8kg). On numerous occasions, Sedy, a scribe of the temple, and the wab-priests Tuty, Nesamun, and Hori removed various amounts of gold from the door-frames. The metal was later melted down before being divided among the robbers and then sold, ensuring that there would be little trace of their crimes. On occasions, the thieves would replace the stolen metal with some material or substance that restored its original appearance in an attempt to hide their misdeeds. What is noticeable is that the authorities did little to stop these thefts, and were often complicit in the crimes. Indeed, the records indicate that bribery was commonplace and officials would turn a blind eye to the incidents, particularly if they received a percentage of the appropriated goods.

On the whole, the thefts were quite extensive and well-organised, and it was not until the reign of Ramesses XI (c.1099-1069 BC) that in-depth investigations of these crimes were instigated. However, even then, many of the perpetrators bribed their way out of trouble, or, if they were dealt with by the courts, any punishment they received is not apparent in the official records.

Finally, on a more philosophical note, the wealth of temples had been accumulated by the imperialism of the New Kingdom, and through religious belief was destined to remain immobilised in the temples and the tombs of the elite. Although some of the stolen spoils were recovered and reused in the temples, much was widely distributed and recycled into daily life, and would have boosted the ailing economy at a time of hardship and decline.

Image: Charles K Wilkinson, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Saints or Sinners?

Should we be surprised to learn that among the priestly classes there were such ‘scandals’? Probably not: every society has its share of such transgressors and their bad behaviour. How common were these misdemeanours? Although we have explored a number of these incidents, when one considers the sheer number of priests who worked in the temples during the entire pharaonic period, it seems doubtful such scandalous behaviour was commonplace. There were probably many priests who were honourable officiants and conscientiously performed their duties; the daily beholding of the statue of the deity was an uplifting experience. We have the example of Petosiris, who was High Priest of Thoth at Hermopolis in the 340s BC. His conduct and accomplishments during a politically difficult time indicate a degree of personal piety and determination to maintain Egypt’s age-old traditions – he was later revered as a leading man in his city.

Finally, what is known about the priestesses in ancient Egypt? Although there is evidence that numbers of women were priestesses of Hathor in the Old Kingdom, by the Middle Kingdom female priestly titles drop to a handful. There appear to be few, if any, examples of wrongdoing or inappropriate behaviour from the limited evidence available.

Further reading:

- S Sauneron (2000) The Priests of Ancient Egypt (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press).

- E Teeter (2011) Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- P Vernus (2003) Affairs and Scandals in Ancient Egypt (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press).

Roger Forshaw is an honorary lecturer in Biomedical Egyptology at the University of Manchester and a former dental surgeon. He studied Egyptology at the University of Exeter and later obtained his MSc and PhD at the University of Manchester. He has published on the Saite Period, medical and dental care in ancient Egypt, and the role of the lector, including a recent paper in Priestly Officiants in the Old Kingdom Mortuary Cult (2022), published by the University of Alcalá in Spain.