Going for gold: mummies from the Graeco-Roman period

The exhibition Golden Mummies of Egypt opens in February at Manchester Museum for its only European showing after an international tour that has included venues in the USA and China. Curator Campbell Price discusses the artefacts on display and their significance to the Greek and Roman Egyptians and to modern visitors.

Mummies, gold, and an obsessive belief in the afterlife – these concepts are all central to our image of ancient Egypt. But how important were they to the Egyptians, and how long did they survive after the last of the pharaohs? A new exhibition, Golden Mummies of Egypt, uses 108 objects to explore expectations of life after death during the relatively little-known Graeco-Roman Period – when Egypt was ruled first by a Greek royal family, ending with Cleopatra VII, and then by Roman emperors (between 300 BC and AD 300).

Wealthy members of this multicultural society made elaborate preparations for the afterlife, combining Egyptian, Greek, and Roman ideals of eternal beauty. Manchester Museum, part of the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, houses one of the finest collections of this material outside Cairo. However, our responses to these objects, excavated at a time of British rule of Egypt in the 1880s-1910s, may reveal more about ourselves than about the people who made and used them.

Cosmopolitan culture

The exhibition opens on the theme of ‘Life in a Multicultural Society’. Egypt was always in contact with neighbouring cultures – it was never as isolated as it is often portrayed. Plentiful evidence survives to show that pharaonic Egypt traded with Nubia and the Mediterranean world for centuries, with many non-Egyptians coming to live in Egypt. But relations between peoples were not always peaceful and there were sometimes violent power struggles. During the Graeco-Roman Period, some of these events were recorded in papyrus documents.

A dynasty of Macedonian origin called the Ptolemies ruled Egypt from 323-30 BC. They built their capital at Alexandria, on the coast looking towards their homeland, but they appeared as traditional pharaohs on temple walls throughout Egypt. They developed farmland in the fertile Fayum area to house new settlers from Greece. Here and elsewhere the Ptolemies promoted the worship of a new, multicultural god called Serapis. A wide range of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian gods were worshipped in people’s homes. Some items buried with the dead offer a glimpse of the things people used in their daily lives.

The afterlife

During the Graeco-Roman Period, preparations for death and the afterlife were influenced by Egyptian, Greek, and Roman traditions. Greeks and Romans had rather bleak expectations for an existence after death. However, the Egyptian afterlife offered them the possibility of rebirth into a bright, perfected version of this world, joining Osiris, the god of resurrection and ruler of the Underworld, for eternity.

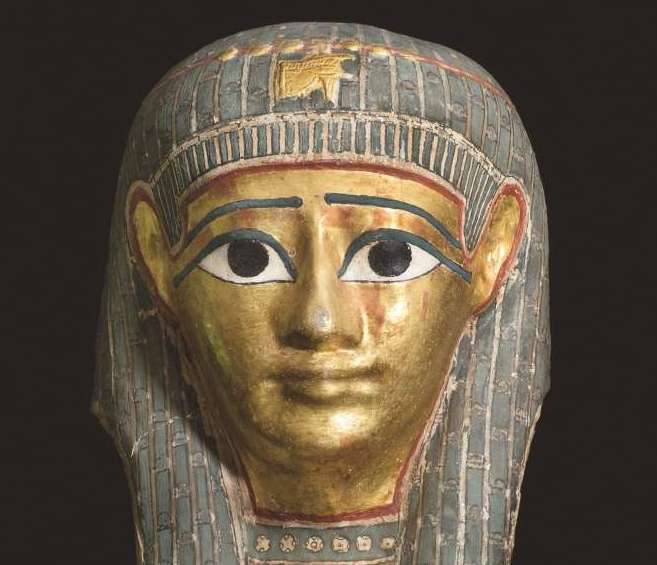

The funeral was an important opportunity to display wealth and status. Coffins, masks, and mummy decorations for the wealthy were bright and eye-catching, made of costly materials. These show the deceased as alive and awake, at the moment of rebirth – magically assuring that this would be the case. People are depicted as perfect versions of themselves: even those who died as children appear as if they had grown up, so they could enjoy the afterlife to the full.

In Egyptian tradition, the gods were immortal. To attain an eternal presence among the gods, the deceased had to – in some sense – become divine themselves. Dead men and women could become one with Osiris, and, by Graeco-Roman times, deceased women could merge with Hathor, the Mistress of the West – where the sun set.

In order to achieve this goal, the body of the deceased had to undergo special ritual preparations, available in their fullest only to the wealthy. The creation and appearance of a wrapped mummy replicated the ancient form of an Egyptian god. Egyptian deities were said to have flesh of untarnished gold and hair of semi-precious lapis lazuli stone. So, for those who could afford to, the coffin, mask or other covering was decorated with gold leaf, and the head covering painted blue. To be armed with this divine imagery was the best means of triumphing over death.

Faces of the dead?

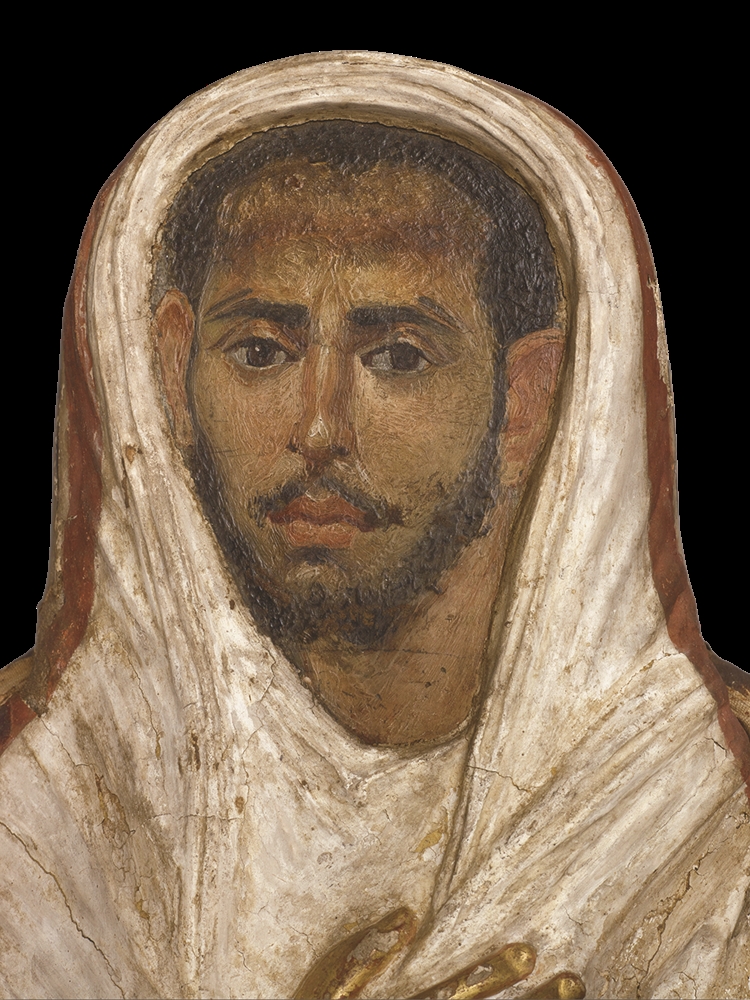

Roman Period painted mummy panels – the so-called ‘Fayum Portraits’ – are among the most striking images from the ancient world. Their discovery in the 1880s changed how people thought about the development of art. Although the portraits have been found at sites all over Egypt, examples from the Fayum region are especially numerous. Each image was built up on a thin wooden panel using a mixture of hot wax and pigment, creating a life-like effect that appeals to modern tastes.

This technique of portrait painting probably originated in ancient Italy. Like earlier mummy masks, portrait panels were originally attached to cover the face of the deceased, to provide an eternal – but probably idealised – face for the deceased. Portrait mummies were rarely identified by name, and we cannot know if the people depicted looked like this in reality, or even if the portraits were painted before death. Despite modern attempts to characterise them in terms of age, race or class, these faces resist categorisation.

Help from the gods

Most people in Egypt were not allowed access to the sacred enclosures of the gods’ temples, and could only see the divine images and hieroglyphs on the monumental exterior walls. Everyday encounters with deities frequently took the form of small terracotta figurines in homes; these appear more Greek or Roman than Egyptian. However, after death, ancient Egyptian gods – usually with their distinctive animal heads – were invoked to help the deceased. Thus, the jackal-headed god Anubis remained popular into Roman times, and is often shown with a key to help the deceased gain entry into the afterlife.

Even after Egyptian hieroglyphs ceased to be commonly understood, they appeared – together with sometimes elaborate images of the gods – on the funerary decorations of the wealthy. These were believed to envelop the deceased with magical, divine power to ensure a successful transition into the afterlife.

Why mummification?

The aim of the ritual of mummification was not simply to preserve the body: it was to create a perfect, everlasting version of the deceased, one that resembled the form of an Egyptian god. In this way, the spirit would have a physical home in which to enjoy the afterlife.

Creating a mummy was an elaborate and costly process, and was only fully performed for the wealthy. Necessary materials included natron (a sodium chloride compound to purify and dry the body), plant resins to make the body fragrant, and large quantities of linen fabric to wrap the body (healing the corpse back to life, like a bandage round a wound). All these processes – purification, anointing, wrapping – were also performed in temples on statues. Such rituals were conducted by specialists in order ritually to transform something (a human corpse, a wooden statue) into a god-like being.

Mummification techniques are often said to have declined during the Roman Period, with focus shifting to the outer decoration of the mummy, but this is a simplistic reading and does not relate to the intentions of ancient people. Today CT scans and X-rays provide an insight beneath the bandages that we were never supposed to gain. For this reason, the exhibition at Manchester Museum will not show any clinical images of human remains.

Collectors and writers

The exhibition closes reconsidering modern reception of the material on display. The many thousands of Egyptian antiquities did not arrive in museums around the world by chance. Archaeologists, workmen, collectors, and patrons all played their part. British colonial control of Egypt – especially between 1882 and the 1920s – enabled Western archaeologists to excavate at sites and to claim a share of their finds from the Egyptian government. In the West, collectors – from national museums to individual hobbyists – all wanted to own a piece of ancient Egypt, and drove the industry of excavation, acquisition, and interpretation.

Flinders Petrie was very interested in the ‘race’ of the mummies he found, interpreting the Fayum portraits, and collecting the skulls of mummies to try to investigate this. He concluded that most were Greek settlers in Egypt, although we now know the elite population of Hawara was much more mixed. Building on Western fascination with Egyptian mummies and immortality, the display of the Fayum portraits even inspired Oscar Wilde to write his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray.

The exhibition opens with the reopening of Manchester Museum on 18 February, and will be on display until the end of 2023.

_______

All images: © Julia Thorne, Manchester Museum

Further reading

A new hardback reprint of Campbell’s 2020 book Golden Mummies of Egypt: Interpreting Identities from the Graeco-Roman Period (reviewed in AE 125) is now available from Manchester University Press: https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk.

Dr Campbell Price is Curator of Egypt and Sudan at Manchester Museum (the University of Manchester) and staff writer for AE magazine.