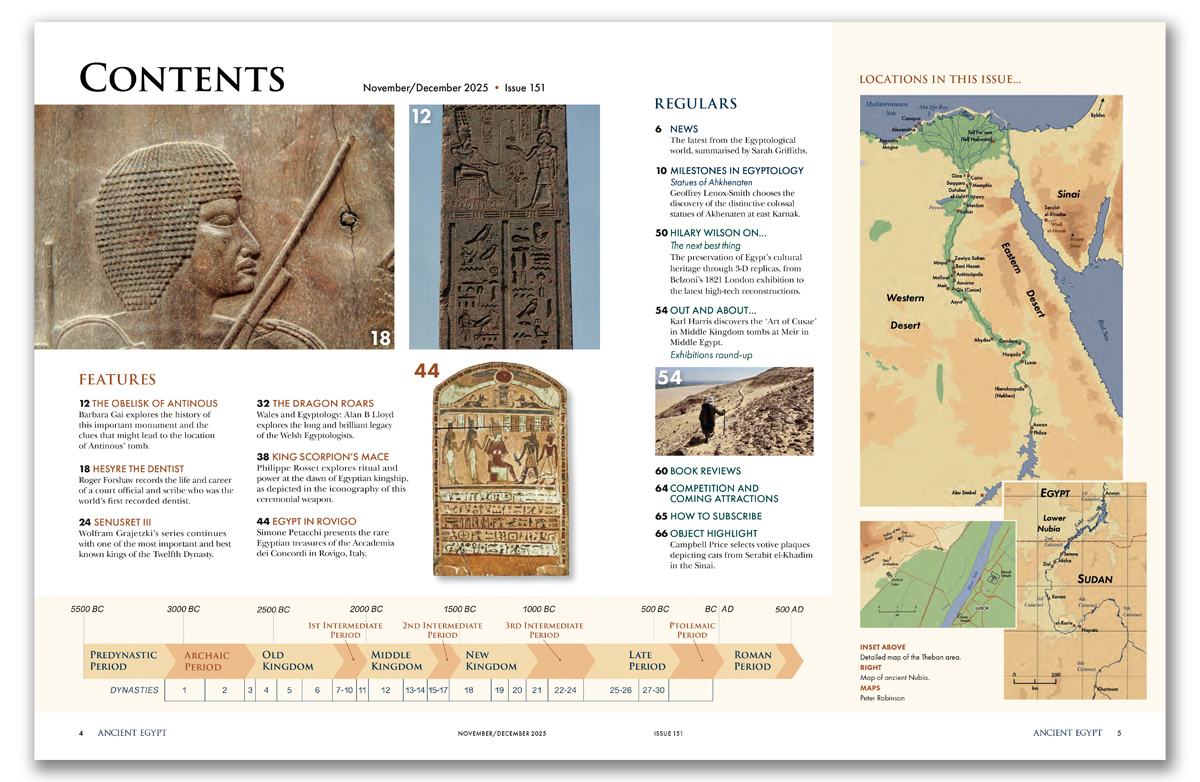

AE 151 - Nov / Dec 2025

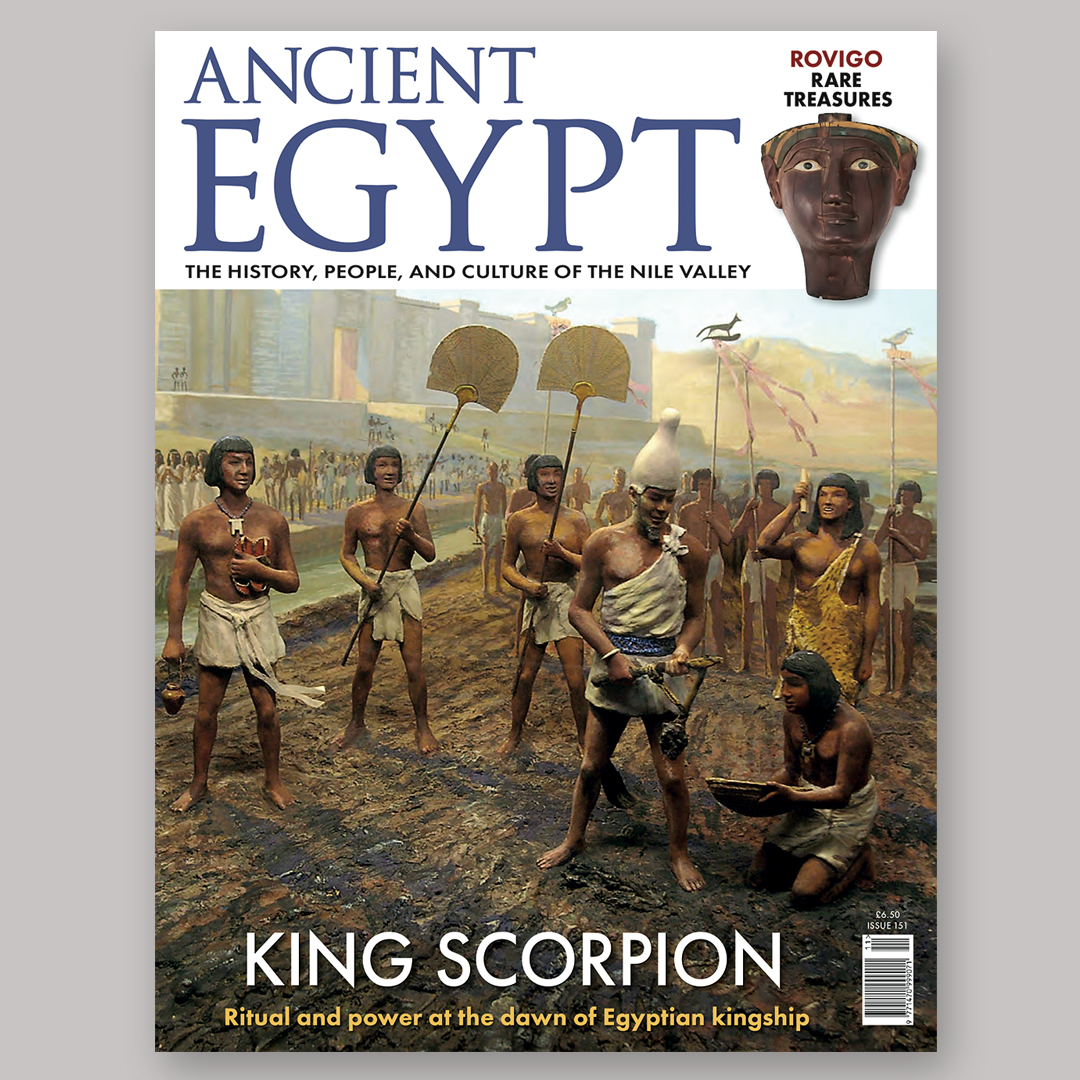

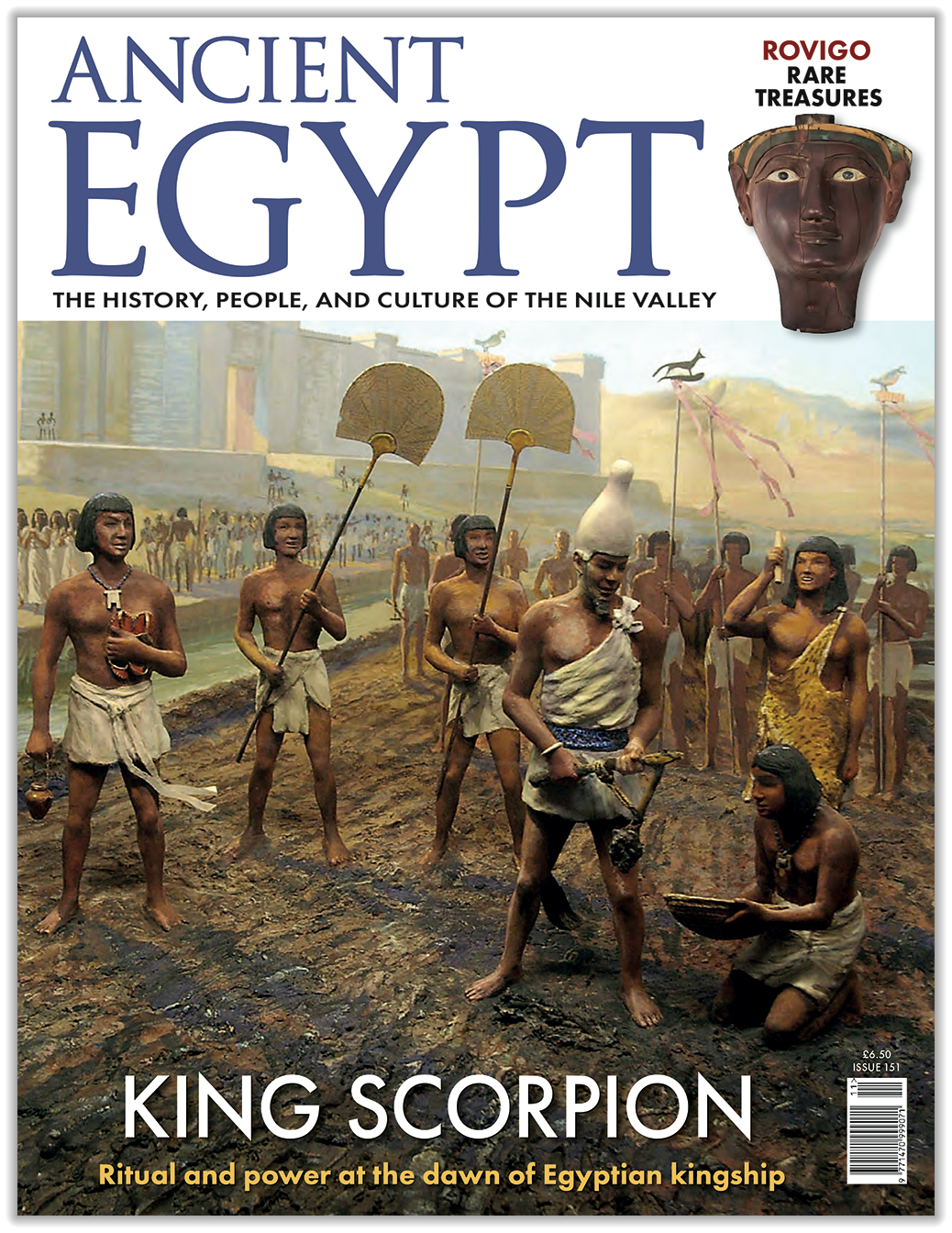

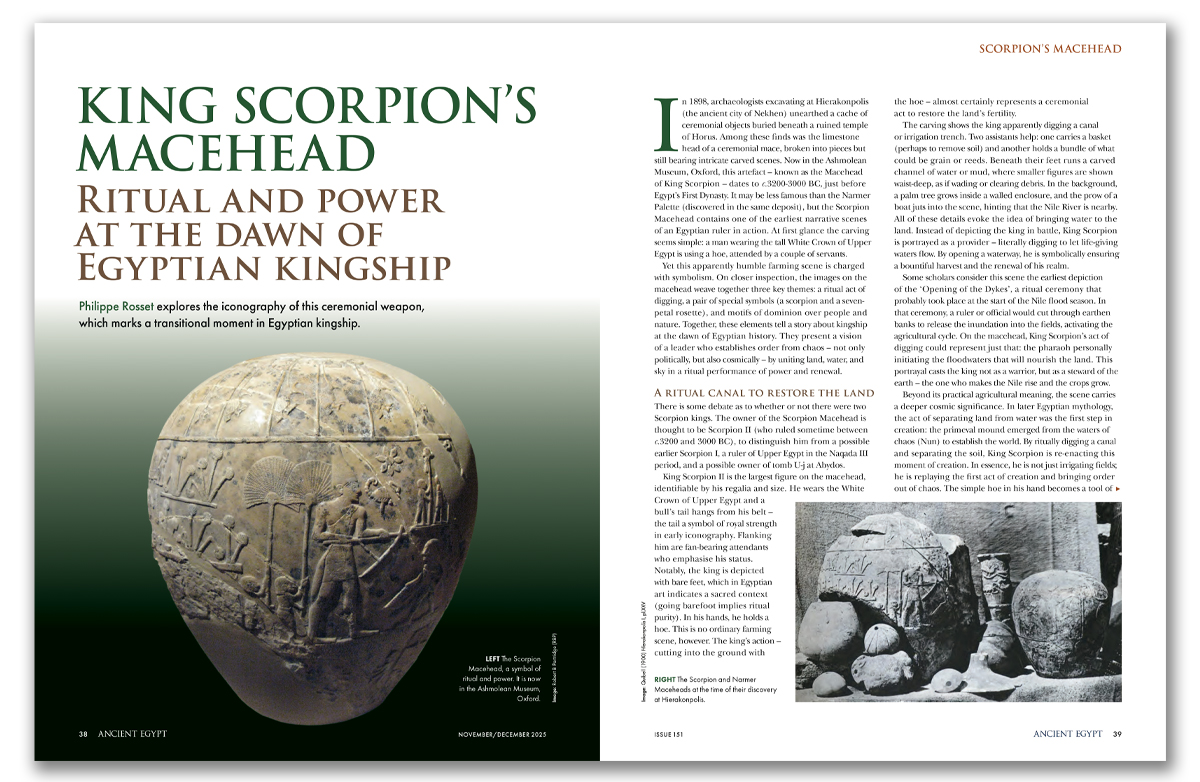

In some ways the Scorpion Macehead that was found at Hierakonpolis, in the same location as the more famous Narmer Palette, is just as important in informing us about the earliest history of the ancient Egyptian civilisation. King Scorpion (so-called because of the scorpion hieroglyph that labels him on the macehead) is shown in the act either of digging an irrigation ditch, or of breaking the wall of a canal and allowing the stored water to flood a field. As Philippe Rosset tells us in his article, the symbolism of this act is difficult to underestimate. It shows that the structure of the state with the pharaoh at its head was firmly established, and that state control of the system of irrigation which made agriculture flourish in a desert environment had been formalised. The diorama featured on the cover of this issue brings vividly to life the scene depicted on the macehead.

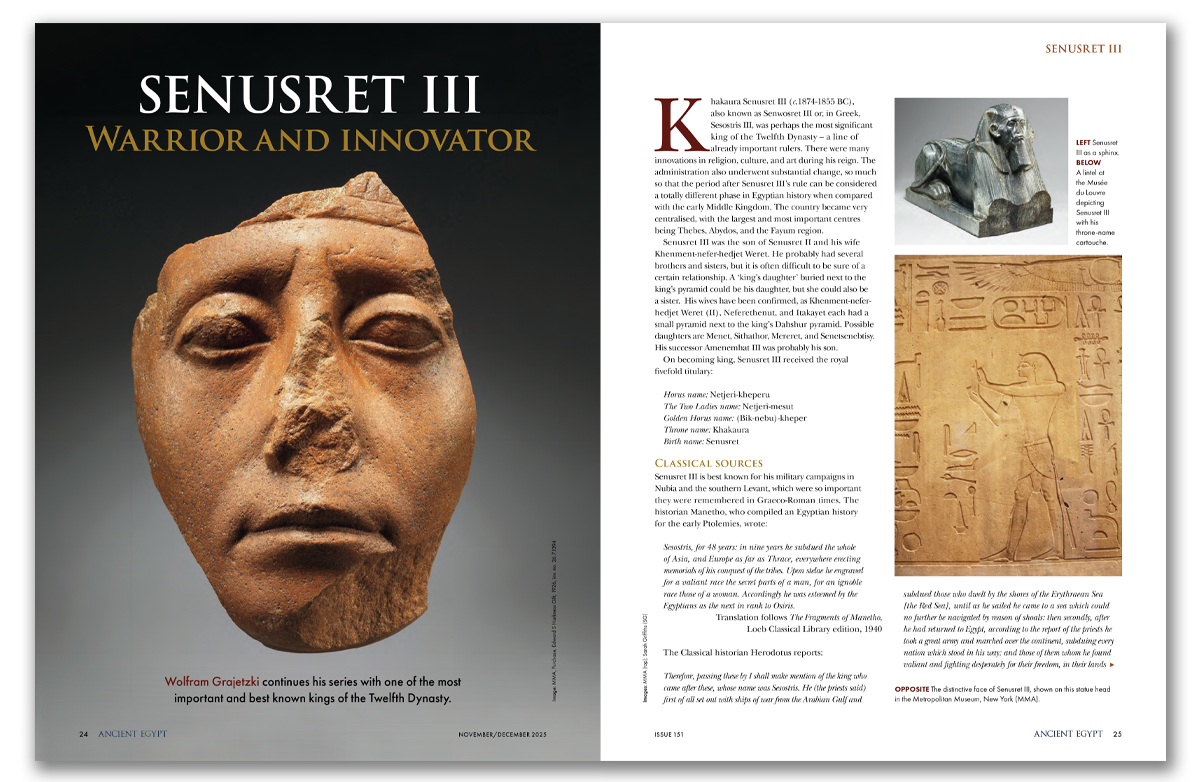

In AE 150, there were several articles that illustrated lesser known but important aspects of Egyptology, and AE 151 continues that theme. Simone Petacchi visits a museum near Venice that contains unique artefacts that are never seen by the general public; Karl Harris takes a trip to tombs in Meir where cobras guard the path; an obelisk dedicated to Hadrian’s lover Antinous rather than a pharaoh is described by Barbara Gai; and former dental surgeon Roger Forshaw describes the unique wooden panels that depict the world’s first known dentist Hesyre. Senusret III, on the other hand, is one of the most significant kings of the Twelfth Dynasty, and was still seen as an inspiration nearly 2,000 years later.

Why should it be that a disproportionate number of prominent Egyptologists have deep connections with Wales? Alan Lloyd lists some of them and investigates the reasons for their interest in the subject. Finally, the general public’s fascination with the ancient civilisation has inspired the creation of many replicas of its monuments, some much less faithful to the original than others, as Hilary Wilson recounts.