AE 139 - Nov / Dec 2023

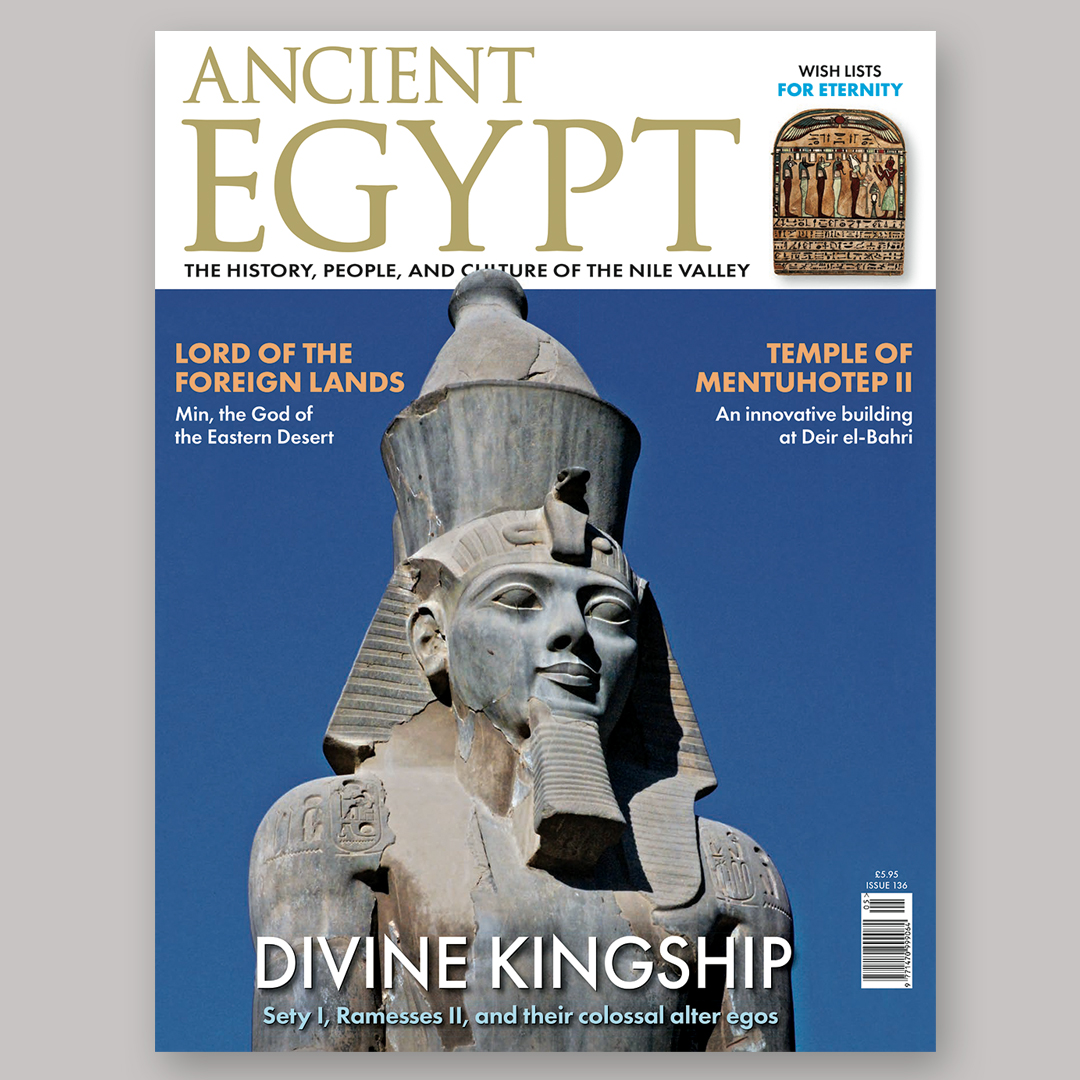

Ramesses the Great enjoyed a very long life and achieved the immortality so coveted by all Egyptians – the cartouche of his name can still be seen on monuments throughout the country. His success as pharaoh, at least in part, can be attributed to the care with which his father Sety I prepared him for the role, as Peter Brand explains.

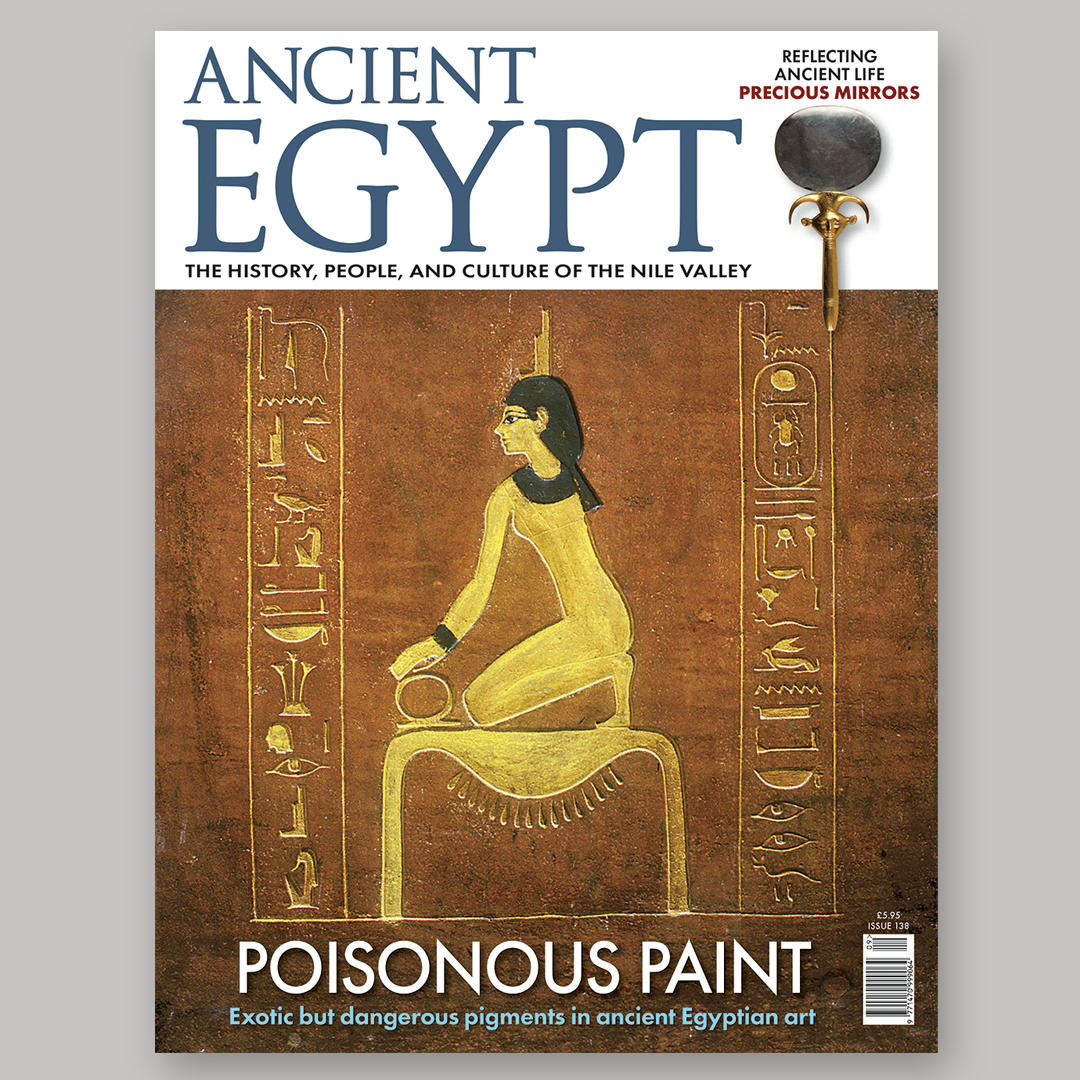

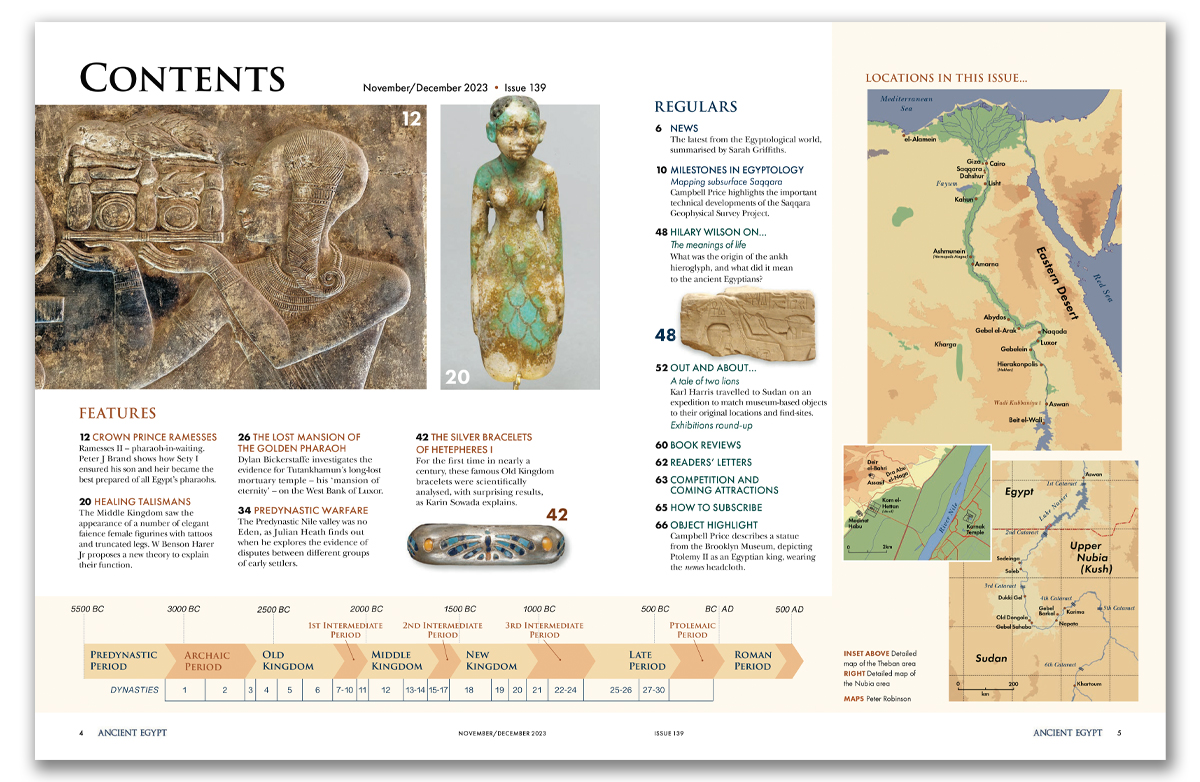

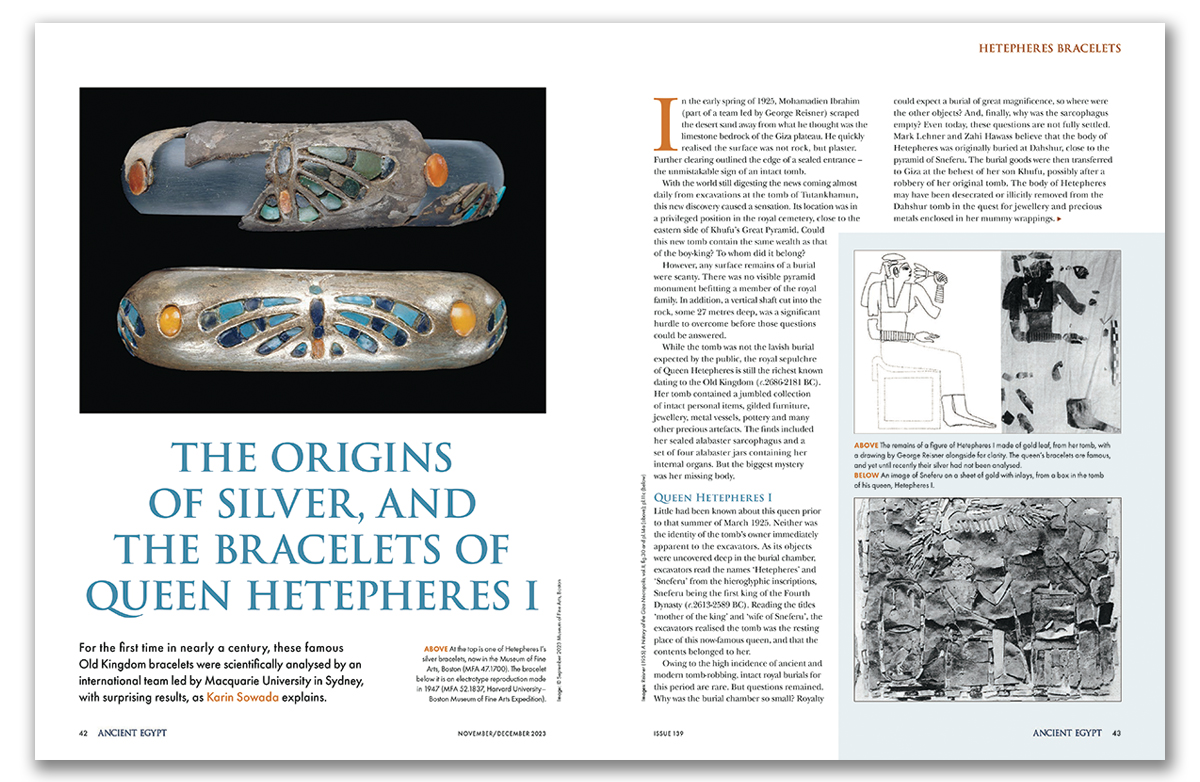

As our knowledge of the ancient Egyptian civilisation increases and modern scientific techniques are applied to existing artefacts, some long-standing beliefs are being overturned. Karin Sowada reports surprising conclusions from analysis of the silver from which Queen Hetepheres I’s bracelets were made. It originated in Greece, proving that trade routes existed much earlier than previously thought. In the past, some small faience statuettes of tattooed women were wrongly called ‘brides of the dead’. Using his medical knowledge, Dr W Benson Harer suggests that they are in fact healing talismans.

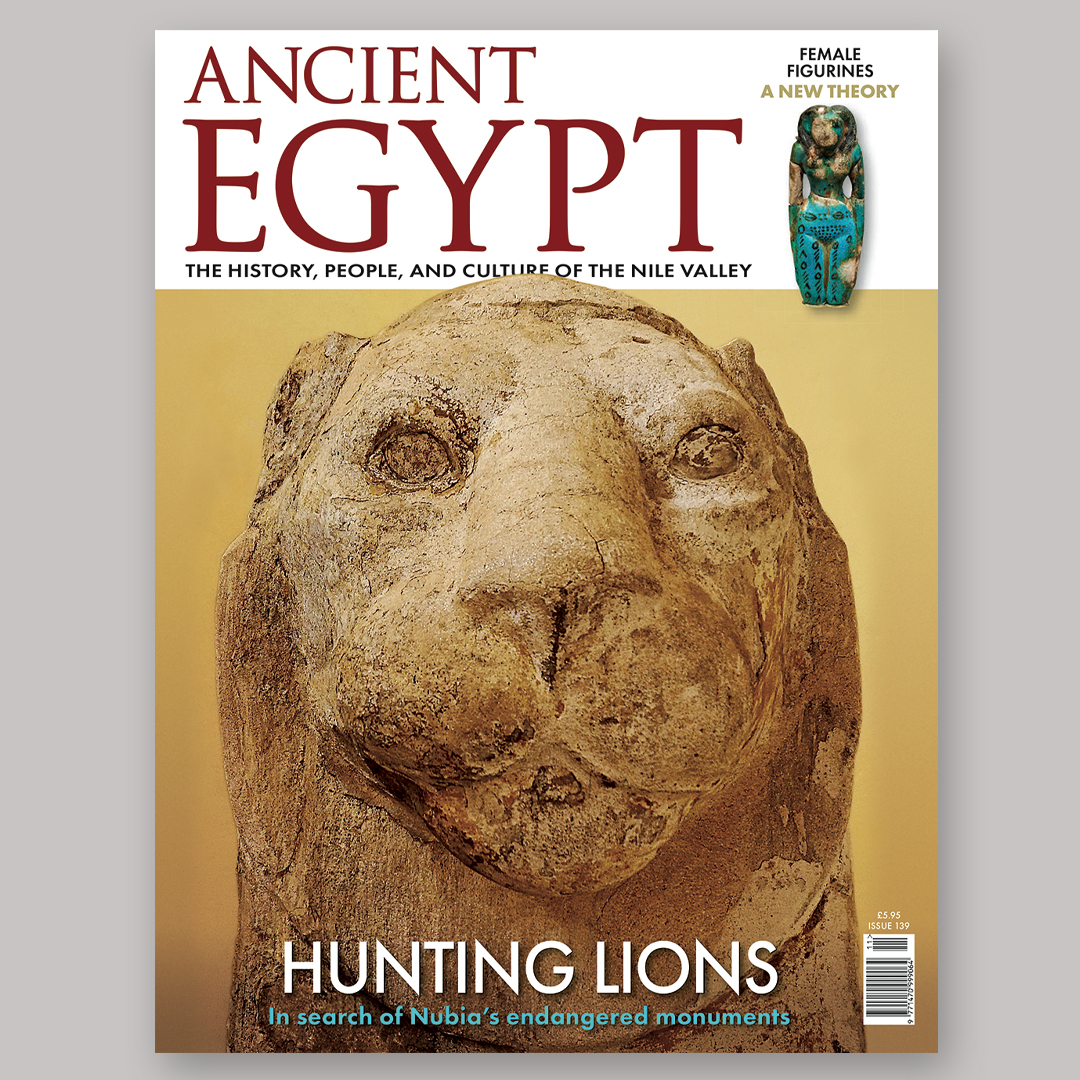

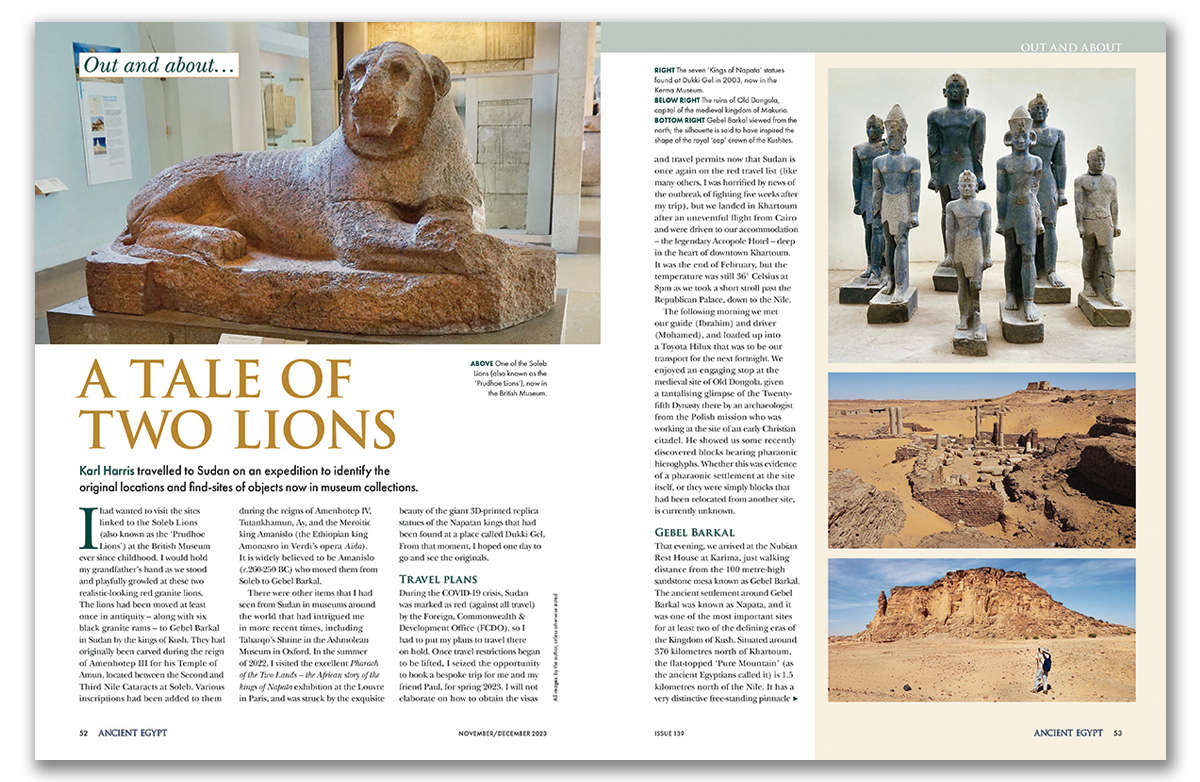

There is much of Egyptological interest to be seen in Sudan, as Karl Harris tells us in his ‘Out and About’ article in this issue. He was fortunate to be able to visit the country before the recent fighting, which has put it off limits.

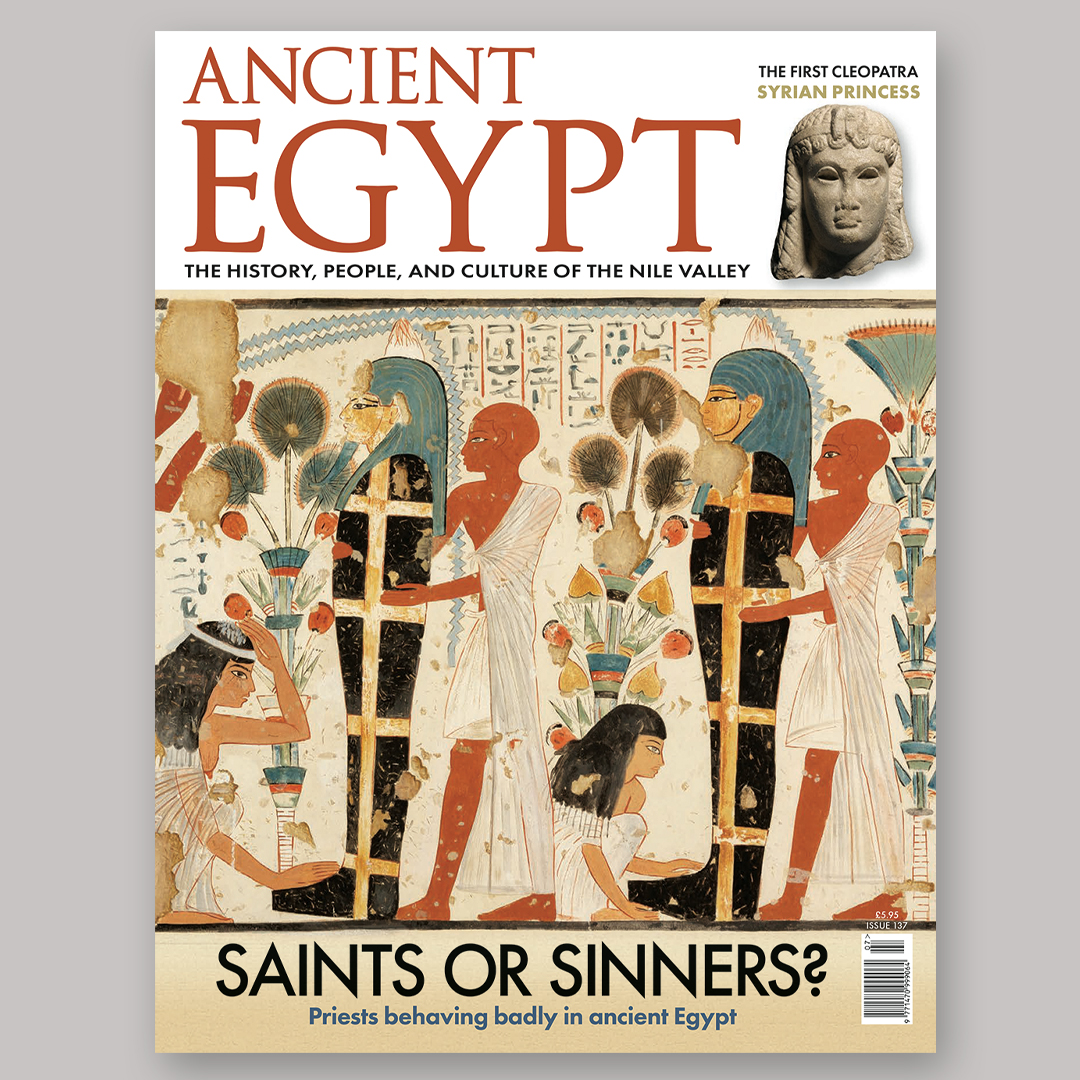

For much of history, Egypt had an uneasy relationship with its southern neighbour, leading sometimes to open warfare. And Julian Heath points out that modern re-examination of skeletal remains has shown that violent conflict was the norm within Predynastic Egypt itself.

On a lighter note, Hilary Wilson chooses the familiar ankh hieroglyph for her article, pointing out that as well as ‘life’, it can also mean ‘mirror’ or even ‘sandal’!