A family of god-kings: divine kingship in the early Nineteenth Dynasty

Peter J Brand begins a new series focusing on the Ramesside Period by exploring the divinity of the early Ramesside kings.

Divine kingship was as old as Egyptian civilisation itself, when the Predynastic kings of Hierakonpolis (Nekhen) ruled as avatars on earth of the falcon god Horus. Pharaoh was entitled the ‘Good God, the Son of Ra’. Egypt’s gods and goddesses were his fathers and mothers. In life he was the incarnation of Horus; in death, his identity fused with Osiris, Lord of the Underworld. But there were limits to royal godhood. Each king inevitably aged, sickened, and died. Many were feeble in body and in mind even before old age overcame them. However, this contradiction between Pharaoh’s human frailty and sublime godhood was not a problem: the divine was understood to inhabit the earthly body, but be quite separate from it. The king’s human self was a mortal vessel containing the divine essence of kingship. Most kings only truly became a god after death.

Cult of divine kingship

In the New Kingdom, the Egyptians developed a sophisticated ideology of divine kingship that was celebrated in royal cult temples built throughout Egypt and Nubia by the pharaohs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties. Amid the increasing wealth and splendour of Egypt’s imperial age, and the evolution of solar religion during the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty, the cult of divine kingship reached a peak under Amenhotep III, especially during his third decade as he celebrated three Sed festivals, and asserted his status as a living incarnation of the sun god on earth. Amenhotep’s cult took a variety of forms, including dozens of royal colossi and hundreds of smaller statues. Among the most innovative aspects of this programme of self-deification was a special avatar of the deified Amenhotep III, worshipped in his temple at Soleb in Nubia: a moon god named ‘Nebmaatra Lord of Nubia’.

Amenhotep III’s successor Akhenaten embarked on a revolutionary, but ultimately unsuccessful religious reformation by replacing Egypt’s pantheon with the unique solar god called the Aten. Two decades later, amid much turmoil at home and abroad, the last three rulers of the Eighteenth Dynasty – Tutankhamun, Ay, and Horemheb – re-established the old gods and attempted to revive the prestige of Egyptian kingship that Akhenaten had so fatally undermined. Of these kings, only Tutankhamun was born a prince, but all three died without a natural heir, passing the throne from one high official to the next. At last, the throne fell to another high official, a vizier and general named Paramessu – better known to us as Ramesses I, founder of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

Sety I

Ramesses I’s reign was all too brief, not even two years, but he had a vigorous heir who assumed power as Sety I. Named after his grandfather, Sety’s son would one day become king as Ramesses II. In the earliest years of the new royal house, it was politically essential for Sety I and Ramesses II to establish their legitimacy to rule. Some might view them as upstarts, lacking pedigree. Ramesses I was the third successive king to assume the throne without royal blood flowing in his veins. Sety I, however, could assert that as Ramesses I had reigned – however briefly – before him, he was the first pharaoh since Tutankhamun to succeed his father.

One way in which Sety emphasised his own rightful status as pharaoh was to honour the cult of his father as a god, in particular as an avatar of Osiris. Ramesses I died before building his own royal cult temples. At Abydos, Sety dedicated a small chapel to his father near his own larger temple, while at Qurna on the West Bank of Thebes, he allocated a suite of rooms in his royal cult temple to worship of his father. In both shrines, Ramesses I appears in the guise of Osiris. The political message is clear: the deceased Ramesses is Osiris, while his living son and successor Sety is Horus.

As part of his ambitious programme to restore the status of Egyptian kingship after the Amarna Period, and to bolster his own credentials as a great Pharaoh, Sety I aimed to revive a style of divine kingship not seen since the heady days of Amenhotep III, on whom he consciously modelled himself. In his ninth regnal year, a year or so before his death, Sety commissioned a multitude of colossal statues from the granite quarries at Aswan, but died before they were completed. He also constructed several temples across Egypt and Nubia of a type called ‘Mansions of Millions of Years’, including the famous Great Hypostyle Hall of Karnak, his exquisite Abydos temple, and his temple on the West Bank of Thebes at Qurna. Each shrine was dedicated to one or more of Egypt’s major gods and to the divine king himself.

At Abydos, Sety I appears both as a god in his own right and as an avatar of Osiris. Likewise, at Qurna, Sety’s divine identity commingles with that of Amun-Ra himself. In scenes of his cultic worship, the deified Sety I is usually identified by his cartouches. A special avatar of the divine Sety I is ‘Menmaatra the Great God’, whose name is written without a cartouche. He appears twice in the Abydos temple. In one scene, he receives worship from the gods Horus, Thoth, and Wepwawet, and from the Iunmutef-priest; in another, he is worshipped by the gods and the mortal Sety himself.

Ramesses II

All the trends that emerged in the royal cult under Sety I, reached their zenith in the long reign of his successor, Ramesses II. Taking the throne in his early 20s, scarcely more than a decade after his grandfather became pharaoh, the youthful king took pains to honour the memory of his father and grandfather by promoting their cult. Ramesses II completed work in Sety I’s unfinished Qurna and Abydos temples. At Qurna, he dedicated scenes in the outer chamber of his grandfather’s cult chambers with images of himself worshipping Sety I and Ramesses I alongside Amun-Ra and the other gods. This conspicuous filial piety bolstered his right to rule. But Ramesses II was not shy about claiming the mantle of divine kingship for himself from the very outset of his reign.

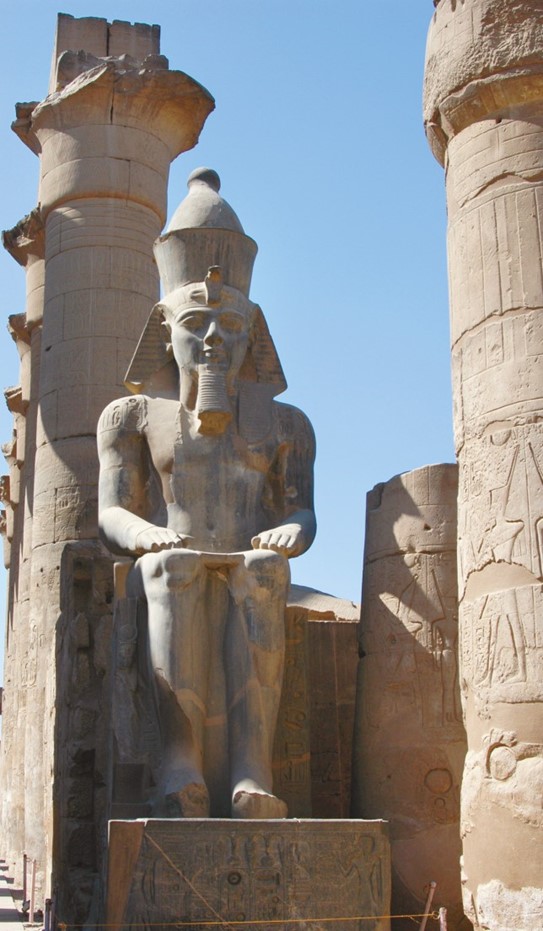

In Ramesses II’s earliest years as king, the colossi ordered by Sety emerged from the quarries to be completed in Ramesses’ name, including four seated giants at Luxor Temple. Each had its own name, modelled on the king’s name, engraved on the statue’s shoulders like a monumental tattoo. The best-preserved is named ‘Ramesses the Ra of Rulers’. Ramesses raised other colossi at temples across Egypt and Nubia, each with a name reflecting a unique aspect of the king’s divine persona. In fact, the same name could be found at multiple sites. Just across the Nile from Luxor Temple, at the Ramesseum in Western Thebes, the famous ruined colossus known to us as ‘Ozymandias’ was originally named ‘Ramesses Ra of Rulers’, as were others at Abu Simbel and Pi-Ramesses.

Colossal statues served both a religious and a political function. They attracted a crowd of worshippers from every level of Egyptian society – from high officials and royal sons to ordinary people. A cache of votive stelae found near the ruins of ancient Pi-Ramesses reveals the broad cross-section of Egyptian society who worshipped the pharaoh’s giant effigies. Colossi stood at the entrances to temples and were accessible to the public. They were often considered ‘hearers of prayer’ – divine intermediaries who could pass the petitions of the faithful to the gods resting within the holy of holies of the temple – an area inaccessible to average Egyptians.

A key aspect of Egyptian deities was the variety of different names, epithets, and visual forms they could take, and their ability to merge with one another. Local manifestations of a god were said to reside in specific cities or temples – so too with the divine Ramesses II. Called by his personal name ‘Ramesses’ or his coronation name ‘Usermaatra Setepenra’, the divine king’s epithets included ‘the God’ and ‘the Great God’. The god-king’s name was written with or without a cartouche, and various avatars were said to dwell in specific temples such as Abu Simbel and Wadi es-Sebua in Nubia.

Artistic representation

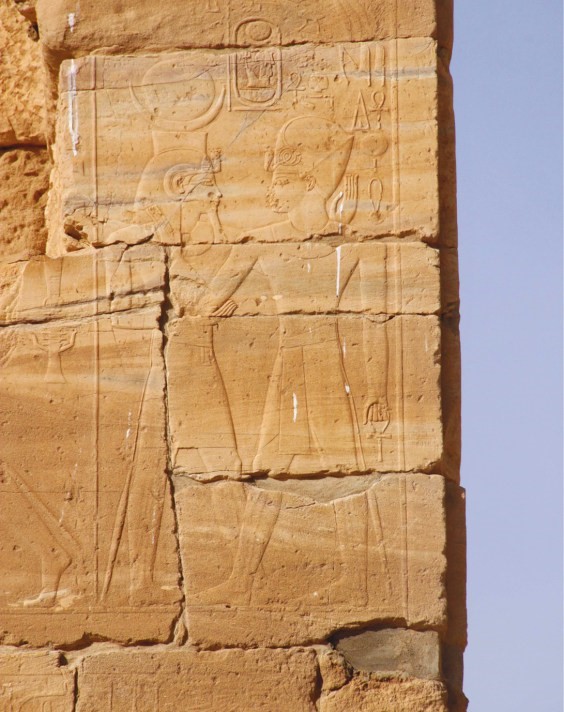

Egyptian artists expressed the complex divine identity of Ramesses II through a rich and manifold variety of imagery. Traditionally, the deified king bore no distinctive costume, crowns, or regalia other than an ankh (sign of life) or perhaps a was sceptre. Under Sety I, the deified Ramesses I and Sety I occasionally mimicked Osiris or Amun in appearance. Now Ramesses introduced a plethora of unique avatars, especially in his Nubian temples. Ramesses II’s name means ‘He Whom Ra Created’, hence solar imagery is a common attribute of the king’s divine alter ego, with sun discs often perching on his wig or crown. Indeed, Ramesses even became a living incarnation of the sun god Ra-Horakhty himself, appearing as the hawk-headed deity with a large solar disc. Ramesses II’s special relationship with Ra-Horakhty extended to the appearance of the king’s sacred barque. Unlike other king’s barques (including that of Sety I, which had a crowned royal figurehead), Ramesses II’s sacred barque sported Ra-Horakhty’s falcon’s head crowned with a solar disc. During the latter half of his reign, even the name of the king’s Delta capital of Pi-Ramesses was changed to refer to the king as ‘the Great Ka-spirit of Ra-Horakhty’.

According to the New Kingdom doctrine of Pharaoh’s divine birth, each ruler was the bodily son of Amun-Ra. To stress this connection, the divine Ramesses often has a pair of curved rams’ horns emerging from his forehead, the ram being Amun’s sacred animal. Like Amenhotep III at Soleb, Ramesses II can also be a moon god, wearing a lunar disc and crescent on his crown.

Ramesses II stressed his divinity further by associating his godly alter ego with Egypt’s other deities. In the temples, wall scenes and statuary groups depict his deified aspect in company with other gods, often receiving worship from his mortal self. A special class of gods and goddesses ‘of Ramesses II’ also proliferates during his reign, including Amun, Ra, and Ptah.

Beginning in the 30th year of his 67-year-long reign, Ramesses II celebrated the first of an unprecedented spate of 13 Sed festivals, the so-called Egyptian royal jubilees. Monumental inscriptions from this period celebrate the king’s godhood in florid poetic style, as with these snippets from his First Hittite Marriage Decree:

Living image of Ra… his flesh is gold, his bones are silver, and all his limbs are iron… a great god among the gods… the living and perfect Ra of gold, the electrum of the gods…

As his mummy attests, Ramesses II became increasingly frail in his later years, suffering from a host of debilitating medical conditions that must have prevented him from fulfilling many of the public duties he performed in his younger days. Nor would the sight of this decrepit old king in his last days have been an inspiring one to his subjects. But the ideology of divine kingship had solutions to this problem. In Egyptian mythology, the sun god Ra himself grew into a doddering old man, stooped over and drooling. So even in his dotage, Ramesses impersonated Ra on earth. And as he became more and more a recluse in his palaces, rarely seen by anyone but a trusted cohort of personal attendants, family, and privileged courtiers, the status of being a living god ensconced in his quarters – like the cult statue of a god in its temple – was the perfect cover for an old king fading into his twilight years.

Over several decades, three generations of the early Ramesside kings nimbly adapted the traditional doctrines of pharaonic Egypt’s divine kingship to meet the political challenges they faced in establishing the legitimacy of their new dynasty. Sety I and Ramesses II worshipped their deceased predecessors as gods even as they established cults of their own deified selves. No other pharaoh in Egyptian history exceeded Ramesses II in the scale and variety of his royal cult, which he expressed through dozens of colossal statues, temples dedicated to his worship, and numerous unique avatars of his divine person. For centuries thereafter, Egyptians remembered him as ‘Ramesses the Great God’.

Dr Peter J Brand is a professor in the Department of History at the University of Memphis, USA, and a director of the Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project. He specialises in the history and culture of ancient Egypt during its imperial age (c.1550-1100 BC) and is the author of The Monuments of Seti I and Their Historical Significance (Brill, 2000). His latest book, Ramesses II, Egypt’s Ultimate Pharaoh, will be reviewed in AE 137.

All images: by the author, unless otherwise stated.